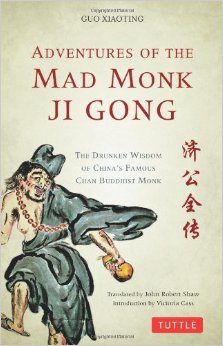

Adventures of the Mad Monk Ji Gong by Guo Xiaoting, translated by John Robert Shaw, Introduction by Victoria Cross, Tuttle Publishing, pp 542

reviewed by Vladimir K

When the twelfth Doctor Who (Peter Capaldi) of the long-running BBC sci-fi program of the same name asks his beautiful young companion, Clara (Jenna Coleman) where in space and time she’d like to go, she asks to meet Robin Hood. The Doctor flies off to Sherwood Forest in the space-time travelling spaceship, the Tardis and, being a sci-fi show, does battle with the evil Sheriff of Nottingham, who is, of course, a vile alien pretending to be human. Throughout the episode, Doctor Who tries to prove that Robin Hood is also an alien, not a real human, just a myth. In the last scene, Robin Hood (Tom Riley) asks the Doctor, “Is it true, Doctor? That in future I’m forgotten as a real man, — I am but a legend?” The Doctor replies, “I’m afraid it is.” Robin thinks for a moment and says, “Hmmm, good. History is a burden. Stories can make us fly… perhaps we’ll both be stories and may those stories never end.” Legends, myths and stories are sometimes more powerful than history itself.

Since the mid-twentieth century there has been a veritable avalanche of books and articles on Zen Buddhism available in the West, in English and other European languages. Koan collections, such as the Bìyán Lù (J. Hekiganroku; E. The Blue Cliff Record

Since the mid-twentieth century there has been a veritable avalanche of books and articles on Zen Buddhism available in the West, in English and other European languages. Koan collections, such as the Bìyán Lù (J. Hekiganroku; E. The Blue Cliff Record

) and Wúménguān (J. Mumonkan; E. The Gateless Gate: The Classic Book of Zen Koans

), have been translated a number of times and studied extensively by Western Zen students. These sayings of the ancient Chinese Chan masters are a cultural treasure of not only China, but all civilization. We also have translations of books on individual masters such as J. C. Cleary’s Swampland Flowers: The Letters and Lectures of Zen Master Ta Hui

(Shambala), Cultivating the Empty Field: The Silent Illumination of Zen Master Hongzhi

, translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton with Yi Wu, James Green’s translation of The Recorded Sayings of Zen Master Joshu

(Shambala), Urs App’s translation of Master Yunmen: From the Record of the Chan Master "Gate of the Clouds"

as well as Japanese masters such as Bassui Tokusho and Arthur Braverman’s Mud and Water: The Teachings of Zen Master Bassui

(Wisdom Publications), and even a number of translations of Dōgen Zenji’s Shobogenzo (for example, see Rev. Hubert Nearman's translation available for free here). Between the numerous translations of various koan collections and the ‘recorded sayings’ of the ancient masters, we have access to hundreds of books on Zen and Chan Buddhism and the important historical figures of Chan and Zen. Throw in possibly thousands of articles on the topic and we have an abundance of literature to peruse. But what we don’t have is a particularly accurate or detailed record of who these Zen masters were as people.

In many cases, the records we do have of the ancient Zen masters were written decades and sometimes hundreds of years after the death of the master. Then, throughout history, the records were added to, tampered with, changed to meet the requirements of the particular Zen sect and, well, what is history and what is myth? As Buddhist scholar John McRae says, thousands of people over centuries were involved in creating the Zen legends that we have today. Furthermore, the more detail in the legend, the less it lends itself to historical accuracy. (McRae, 2003, p. xix) We shall never know what Linji Yixuan (d. 866) thought about his parents, or what his childhood was like. Did Nanyuan Huiyong (860-930), the strict and uncompromising teacher in the Linji lineage ever fall in love with a Buddhist nun? When Muzhou Daoming (780-877) broke Yunmen Wenyan’s (864-949) leg the record shows that Yunmen attained enlightenment. Or did that occur later and at the time Muzhou slammed the door on Yunmen’s leg, did Yunmen yell out “Bloody hell! What have you done?” or perhaps something stronger, but something very human. The details we get in modern biographies are lost forever when it comes to the ancient Zen masters. Modern Zen masters, on the other hand, are being revealed in considerable detail. In the age of the internet, there is nowhere to hide.

Mad Monk Ji Gong is a perfect example of the man lost in the legend. There is very little left of the man but there is a considerable body of work on the legend. Ji Gong (also known as Daoji; born as Li Xiuyuan) lived from 2 February, 1130 to 16 May, 1207 1 He was ordained as a monk at the famous and still extant Lingyin Temple (founded in 328) in the hills just outside of Hongzhou. His drunkenness and proclivity to eat meat eventually had him thrown out of the temple and he spent the rest of his life wandering around in tattered robes helping people with his magical powers.

Ji Gong has a special place in Chinese literature and religion. He went from being a drunken, meat-eating Chan monk who was thrown out of his temple in disgrace to becoming a virtual ‘god’ to a wide spectrum of Chinese society. He was not included in any Buddhist histories of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) and appeared only in Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) writings but without any biographical details. An oral history built around the antics of the monk was popular among the masses and by 1569 the novel Qiantang hu yin Jidian Chanshi yulu was published. Later novels such as Zui puti (before 1673) and Jigong quanzhuan (1668) cemented his reputation as both an eccentric and a saviour of the weak and poor.

However, perhaps the most important is the version this English translation is based upon, Guo Xiaoting’s Pingyan Jigong zhuan (The Complete Tales of Lord Ji)(1898-1900). Culling centuries of oral story-telling, this is a rollicking tale of spirits, magic and martial arts. Although the original stories were based in Hangzhou, Guo was a Beijing story-teller and, as the Introduction by Victoria Cass points out, the flavour of the novel is of a “peculiar urban marriage of Hangzhou and Beijing”. (p. 17) This admirable translation by John Robert Shaw maintains the boisterous flavour of the original tales, salted as they are with rogues and bandits, women both beautiful and plain, pompous wealthy who are brought down a notch or two, magicians and potions that heal and kill, and an array of eccentric characters of which Ji Gong is but one, albeit the most important. While we have lost Ji Gong the man, we have gained something far more significant — entertaining, humorous tales that have outlived their hero and provided pleasure to millions over millennia. Shaw’s translation now makes this trove of stories available to a new readership. Tuttle Publishing is to be congratulated on bringing this volume to the English-speaking public.

1 Victoria Cass’s Introduction states that he was born in Hangzhou “perhaps in the year 1130. The dates I’ve used above come from Wikipedia and, being so exact, are suspect.

References and Further Reading

McRae, John R., 2003, Seeing through Zen: Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism , University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles

Shahar, Meir, 1998, Crazy Ji: Chinese Religion and Popular Literature (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph)

Harvard University Asia Center, Cambridge